Wink writes:

Vincent and Daniel,

I am willing to bet that you would not pass the Toxo/Sex/Internet study if it came through an oversight committee you were on. If so, why give it the TWIP bump?

Wink Weinberg (Atlanta)

Anthony writes:

The (lucky number 7) worms collected by Dickson Despommier (then in his technician phase (1962?)) from the woman in the hospital were tapeworms, not flatworms.

https://www.microbe.tv/twip/6-tapeworms-the-long-and-short-of-it/

FWIW.

Noah writes:

Chinese text printed on the “sticker test” cellophane

第一日

dìyī rì

first day

Day one

蟯蟲檢查玻璃紙

náochóng jiǎnchá bōlizhǐ

pinworm check cellophane

Check cellophane for pinworms.

Sincerely, Noah

Case guesses:

David writes:

Dear Hosts,

Although the hiking woman from Colorado featured in the case of TWiP 134 uses iodine tablets while drinking water from streams, the symptoms she presents seem to point to a classic case of giardiasis (or beaver fever). She likely caught the parasite on one of her summer hiking expeditions after drinking stream water contaminated with the infective cyst stage of the Giardia parasite.

The Giardia trophozoites colonize the duodenum and jejunum in the small intestine and prevent host nutrient absorption, which causes gastrointestinal symptoms such as sticky, foul-smelling, fatty diarrhea (or steatorrhea), abdominal pain and nausea. Cysts are then passed into environment along with the feces, and the life cycle can continue.

Diagnosis for this parasite can be obtained through stool examination, ELISA testing, and an entero-test using a thread in a gelatin capsule that has one end taped to the inside of the patients mouth. The thread is later extracted and examined for the presence of trophozoites.

Treatment for the normally self-resolving giardiasis include a nitroimidazole medication (such as metronidazole, which is considered a first-line therapy by the CDC); however there has been recent evidence of drug resistance developing in Giardia.

Thank you once again for the informative and educational podcasts.

Sincerely,

David P

Molecular Helminthology Lab at Tufts Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine

Octavio writes:

Dear Professors,

About a month ago, I came across the Podcast “This week in Parasitology”, and it has since become my loyal, entertaining, and extremely educational travel companion during my usual 3 hours-long driving around beautiful Portugal, the place where I send you my warmest regards from.

I am a Veterinarian, after a few other professional sidesteps, and I felt compelled to write you today, after hearing Professor DesPommier introduction in the first episode of TWiP, when he answered to Professor´s Racaniello question on why had he become a Parasitologist; His answer had to do with “doors opening”. A great story with somewhat of an emphasis on the importance of being in the right place at the right time, which in my opinion seemed to neglect all the work, dedication and talent the Professor has. A sentence ascribed to Thomas Jefferson goes like “I’m a great believer in luck, and I find the harder I work the more I have of it” and I believe this is also the case with Professor DesPommier as with illustrious Professor Racaniello and Professor Griffin.

As I said, I had a few other jobs before and in order to become a Veterinarian; I was a tomato paste factory worker, worked in restaurant kitchens, I was (and still am) a certified commercial diver, worked in private security, I held a couple of office clerk jobs, managed a bookstore, among other “survival experiences” that (in some cases thankfully) time ensured to blur out from my memory.

Nowadays and since 2013, I am working for a veterinary pharma company as a lecturer on their products, particularly in ectoparasiticides, the big fat teat on which 40% of all the vet pharmas gladly suck (smile).

As long as there are fleas and ticks in this world, there will be business – and that’s not only because of the extraordinary biology, adaptation and resilience of these amazing and terrible creatures, but also because of the incredible misinformation, lack of information, or, as I find more frequent, utterly bewildering ignorance of the common citizen on the matters of parasites (parasites of their pets, internal or external, and parasites of their own).

I get a great pleasure and reward from what I do, because even within the constrains of a commercial activity, I feel that, every time I speak with someone (a pet owner, a Pharmacists, a Veterinary colleague, Technician or Nurse, an over the counter retailer, or whomever) I do my best to share with them my knowledge; It is a microscopic knowledge when I compare it with the likes of you three Gentlemen: I just hope it may be a microscopic embryonated egg of knowledge I can lay on my listener’s mind,and that it may hatch onto something useful and with relevance for the “one health”, just as you do with TWiP.

You do a truly great Service, and I learn every single time I listen to you. Please, keep on infecting us with your embryonated eggs of wisdom!

So that this already long message is just not a kilometer-long drooling-over-you exercise, I would like to add my hunch on what may be the cause for TWiP 134 case study – the fatty buoyant feces.

My guess goes to Giardia duodenalis, probably contracted due to consumption of water not completely treated with the iodine tablets this patient referred using, a situation described in the 1997 paper by Gerba, Johnson and Hasan “Efficacy of iodine water purification tablets against Cryptosporidium oocysts and Giardia cysts” (attached).

The epidemiological cycle is another case that reveals the intricate connections between human and wild fauna. In Urquhart’s Veterinary Parasitology it reads “There is evidence from the USA that Giardia from man which gain access to municipal water reservoirs may successfully infect wild animals, especially beavers. These then act as a source of contamination of domestic water supplies.”

Giardia trophozoites (Greek Throphós – the feeding state) should be the responsible for the duodenal, jejuneal (jejunii?) and ileal epithelial villi flattening with compromise of intercellular tight junctions, leading to malabsortion and steatorrhea.

Cryptosporidium would also be a suspect, but it is unusual that immunocompetent individuals should develop clinical disease.

The definitive diagnosis could be established by fresh stool smear examination, despite difficult, because the protozoans are very small (~15 micrometers), may not be passed in every sample, and this sample must be examined within 30 minutes after collection. Patience and systematic methodology are required. They are, nevertheless, very beautiful to watch.

In cats we have an ELISA fast test for Giardiasis, so I imagine quite more sophisticated kits exist for humans, including DNA amplification techniques.

If the diagnosis is confirmed, the anti-flagellated anti protozoan antibiotic metronidazole could be used to the treatment.

That is all for now.

I bid you farewell, and I am

Yours, “parasitophically”

Octávio Carraça Pereira

Post scriptum: “Pereira” is my surname and it means “Pear-tree” – almost a DePommier’s cousin 🙂

My middle name, nevertheless, “Carraça” (it could be read karrassa) means “tick”. Yes, I am a Veterinarian named Tick, who works with ectoparasiticides – I would not go so far as to say what Professor said about chance, fortune, fate or “Fado“, but it sure is quite a gag…

John writes:

Dear doctors Twip,

I think that the woman with the lighter-coloured, foul-smelling, sticky, floating stool from twip 134 has giardiasis.

The description of the stool seems to match steatorrhea (presence of excess fat in feces) which is characteristic of giardiasis. She had cramping and nausea which are also associated with the parasite.

She also consumed water from streams during camping trips (which may have been improperly treated)

Diagnosis can be made by direct microscopic observation of the trophozoites or cysts in a stool sample, by ELISA antibody test or by the delightful (though possibly obsolete?) string test.

The string test involves swallowing a gelatin capsule attached to a string. The string is taped to the subject’s cheek and the capsule is digested and travels down the gut. The string remains in place for several hours and is then withdrawn and the absorbent string is examined for trophozoites or cysts. Lovely.

According to Parasitic Diseases 6ed, treatments for giardiasis include metronidazole and tinidazole, as well as paromomycin for pregnant women.

Regards,

John in Limerick, Ireland where today the weather is 15° C with torrential rain after a week of clear skies and 23° C

P.S. I was listening to the team on TWiV discussing a paper a few episodes ago and Vincent mentioned that two of the authors had ascaris. My first thought that flashed into my head was “that’s an odd thing to say but albendazole or ivermectin should clear it up”. Of course, what Vincent actually said was that the authors had asterisks. They were joint first authors. I’ve been infected by Twip.

Marcia writes:

Giardia lamblia

Johnye writes:

Good morning,

As always a pleasure to listen and learn.

As I listened to the Case Study for TWiP 134, it struck me that a more objective description of the patient’s stool might have been helpful. Dr. Griffin do you ever use the Bristol Stool Chart? I’ve found it very helpful in pediatric and adolescent medicine as a way of clarifying what a patient or parent is describing as abnormal. It is also something medical students and residents find interesting and, hopefully useful.

I’ve included 2 examples of the stool chart. There are many others that may be more or less appealing.

Now to think more about the clinical scenario and possibilities.

Best from Boston and Cambridge where it is currently mostly sunny and 18C.

Johnye

(Your Cambridge Pediatrician)

JB writes:

Hey hey, Doctors!

I’d like to make a guess about the case study from episode number 134, the woman from Colorado experiencing weeks of foul-smelling loose stools.

The duration of her symptoms, as well as a few other facts in the case, has me leaning towards a specific diagnosis.

Floating, light-colored stools sounds like classic steatorrhea, and excess fat could also lead to an increase in “stickiness”. Many parasites can cause malabsorption in the intestines that could lead to steatorrhea, and some of them are water-born. What strikes me is that even though multiple people drank from the same water source, she became ill when her fellow hikers did not.

Had the entire party gotten sick, I would have suspected cryptosporidium. From what I’ve read, standard iodine disinfecting procedures aren’t very good at killing some crypto. If there were a lot of crypto cysts in the water, most everyone would likely have been infected.

The fact that only she got sick (and that only she drank out of her water bottle) leads me to believe that she did not practice sterilization as thoroughly as she may wish she had done.

So a freshwater-borne parasite that is easily killed by thorough iodine sterilization, and causes weeks of foul-smelling steatorrhea? I’m going with a diagnosis of beaver fever, aka giardiasis.

Thanks for all the great work, and here’s to many more wonderful episodes!

JB, Philadelphia

Iosif writes:

Dear Twip Team,

My guess for this week’s case is that our patient has a giardia infection. Cryptosporidium and giardia can both be obtained from dirty stream water and are more resistant to iodine treatment than most organisms. The giveaway is the fact that this diarrhea has been going on for a while and that the stool has turned fatty. The diagnosis can be made with a stool O&P or an ELISA. Treatment is with metronidazole.

Sincerely,

Iosif Davidov

Hofstra SoM Class of 2018

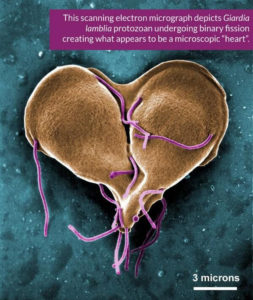

P.S. I found this picture of giardia that I think would have been more appropriate a few months ago, but it was too good to pass up.

Mark writes:

Hello to This Week in Parasitology Hosts Vincent and Daniel,

Be nice to Dickson who is away traveling the world.

Below is my diagnosis for the case study presented by Dr. Griffin in episode 133. Late in the show, you, Vincent, requested listeners to send in an audio file with their diagnosis.

I am having fun by generating an audio file for this letter on my Mac using Siri’s voice. Let us see how Siri pronounces the names of worms that are suspected in this case. Those names are taneia solium, taneia saginata, or As-car-is lum-bri-coi-des.

Eggs of these parasites are spread through contaminated water, food, or soil. Daniel’s case notes indicated the young patient lived in a rural area, in a house with dirt floor, and drank untreated water from a stream. This establishes risk factors and possibility of infection.

Given that she is physically smaller than a younger sister indicates a nutrition problem. Her protuberant belly, hard to the touch, is consistent with a large mass of parasites in her intestines.

There are three candidate worms. We need to start to eliminate some. The girl’s diet is described as plantains, rice, beans. This eliminates taneia saginata which passes from cow to human during its life cycle. Taneia solium is eliminated as it passes from pig to human during its life cycle. This leaves ascaris lumbridoides

The final piece of evidence is that the girl’s mother observed a long, moving worm in the girl’s feces. To me, this piece of evidence validates the diagnosis above. As described in “Parasitic Diseases Sixth Edition” T. saginata is a segmented worm and its proglottid pieces may be observed in feces. T. solium is also a segmented worm and can be eliminated for the same reason. This leaves As-car-is lum-bri-coi-des as the parasite infecting the young girl.

The CDC’s website lists treatment with albendazole, mebendazole, or ivermectin as treatments while noting that the FDC has not approved Albendazole for treating ascaris.

In ancient history, when I started listening to TWiP, Dickson described Ascaris lumbricoides in episode 21. The episode’s image was a disgusting looking jar filled with dead worms. For those interested, I found the URL — it is:

www.microbeworld.org/podcasts/this-week-in-parasitism/archives/854-twip-21-the-giant-intestinal-worm-ascaris-lumbricoides

Keep up the good work, and be nice to Dickson.

Mark

Anthony writes:

Here’s a Believe It or Not feature. A freshwater mussel produces a fishing lure to attract fish to be infested with the mussel eggs:

http://molluskconservation.org/MUSSELS/Reproduction.html

And

http://www.theherald.com.au/story/4647986/blackalls-bat-study-to-look-for-parasites/

Blackalls Park flying fox study to test for waterborne parasites